This is the final entry of Know-It-All, a zine about obsession and fandom. Here I (me, Camille) attempt to explain what this project was all about, and I talk a little about Alice in Wonderland. Know-It-All zine is best read in print. To order a copy, go here. If you’re interested in contributing to issue 2, drop me a note!

As a professional reader, this is how I read: I pick up a book, read the first paragraph, form a judgment on the prose style, continue through the first page, and decide whether what the author promises to tell me is worth knowing at all. If it is, I go on, skimming the pages with increasing velocity like a skier hurtling down a mountain, briefly touching down at the top of each chapter to get my bearings. When I feel I’ve encountered enough of the book to understand how well it has served its intended purpose, I abandon it to my pile of discards for donation to the sidewalk.

I hate reading this way, to be clear. It’s a method that is efficient at picking out books “of interest” in the industry, or for forming a quick appraisal of a literary product. But it transforms reading into a dull chore, underlining every sentence with impatience. I’m aware that when I’m reading like this I’m not very good company for the author, that other mind eager to commune with me through the page. I’m constantly interrupting the text to voice my own reactions instead of listening to what it has to say.

When I was a child, I was terrible at that elusive quality my parents called “social skills”—hygiene, answering the phone, ordering food in restaurants—but I was good at reading. I would pick up a book and read it, then pick up another book and read that, and so forth. It was easy. It had no greater purpose. Whether I liked or disliked the book, whether I learned something or not, didn’t matter to me as much as just reading more.

For that reason, my favorite thing to read was a lengthy book series, or authors who’d written a lot of books. I was the kind of kid who spent every weekend in the library working methodically through the stacks. I read some one-off titles: The Phantom Tollbooth, Five Children and It, Just So Stories. But I got most excited for the promise of infinite pages. There were fourteen of L. Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz books. A couple dozen Roald Dahl books. Twenty-nine Encyclopedia Brown books—each story of which could be solved in about five seconds, so that’s why I needed so many. Sixty-two Goosebumps books, which I thought were trash—a snob even then—but also painless, as I had a system for knocking each title out in under an hour. Fifty-eight Sherlock Holmes short stories, plus four novels. Sixty-some Agatha Christie novels. More than a thousand pages of Lord of the Rings. (Don’t ask me about Harry Potter—I’m too old for that.)

I don’t read this way anymore. These days I expect to get something out of my reading. I pick up a book with intention. But I remember this childhood way of reading with fondness. It was almost mindless. I didn’t have to select the “best” book to read next—they were basically chosen for me in advance. It was not educational, or not purposefully so. It wasn’t fandom, nor was it an obsessive mania. It was just a useful sort of organizing momentum to give structure to the part of my life I spent with books. A way of reading to keep reading.

***

There was another kind of reading I did that went down, not across—down like into a rabbit hole. Lewis Carroll published only a handful of books, and aside from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, most of them were long poems. (Or mathematical treatises published under his real name Charles Dodgson.) His body of work did not offer a lot of pages to occupy me. But I read Alice in Wonderland again and again, and as one of the most re-issued children’s books there are many versions to read with ever-new illustrations to pore over. Each version I see, I read it over again.

It seems possible that my whole life was shaped by this single book. I read Alice in Wonderland when I was eight years old, and that is the reason I started writing poems, and then stories. It is the reason I got into puzzles. It developed my taste for humor and whimsy and logical contradictions. It is probably the reason I took several classes in symbolic logic in college, in defiance of the advice of my counselor, and also why I named my college literary magazine Mish-Mash (the name of the family periodical that a young Dodgson published with his siblings), and maybe why my curiosity about animals resembles that of a Victorian naturalist’s, and probably also a little bit of why I have recently developed an interest in the fly agaric mushroom.

Alice in Wonderland is a children’s book, but it is not only for children. It doesn’t condescend to children with simple language or easy lessons. It doesn’t contain moral instructions or explanations about how the world works. Quite the opposite: Alice tramps through Wonderland insisting on respecting a code of manners and the known laws of physics and is ridiculed at every turn for her blind rule-following, her lack of imagination. She is impetuous and naive; she devolves into tantrums and crying fits. She wants sweets. She wants to go home. She insults the Queen. As a strict abider of rules myself, this behavior was mildly titillating. And the book seemed to acknowledge the frustratingly backwards conditions of childhood. The creatures of Wonderland tolerate Alice’s antics with mild contempt. She is both an annoying brat and an innocent little girl lost in a hostile world. For all its charms, Wonderland operates like a game played by despots according to nonsensical rules that everyone but her understands. Why—is she stupid? Are the rules stupid? Either/or.

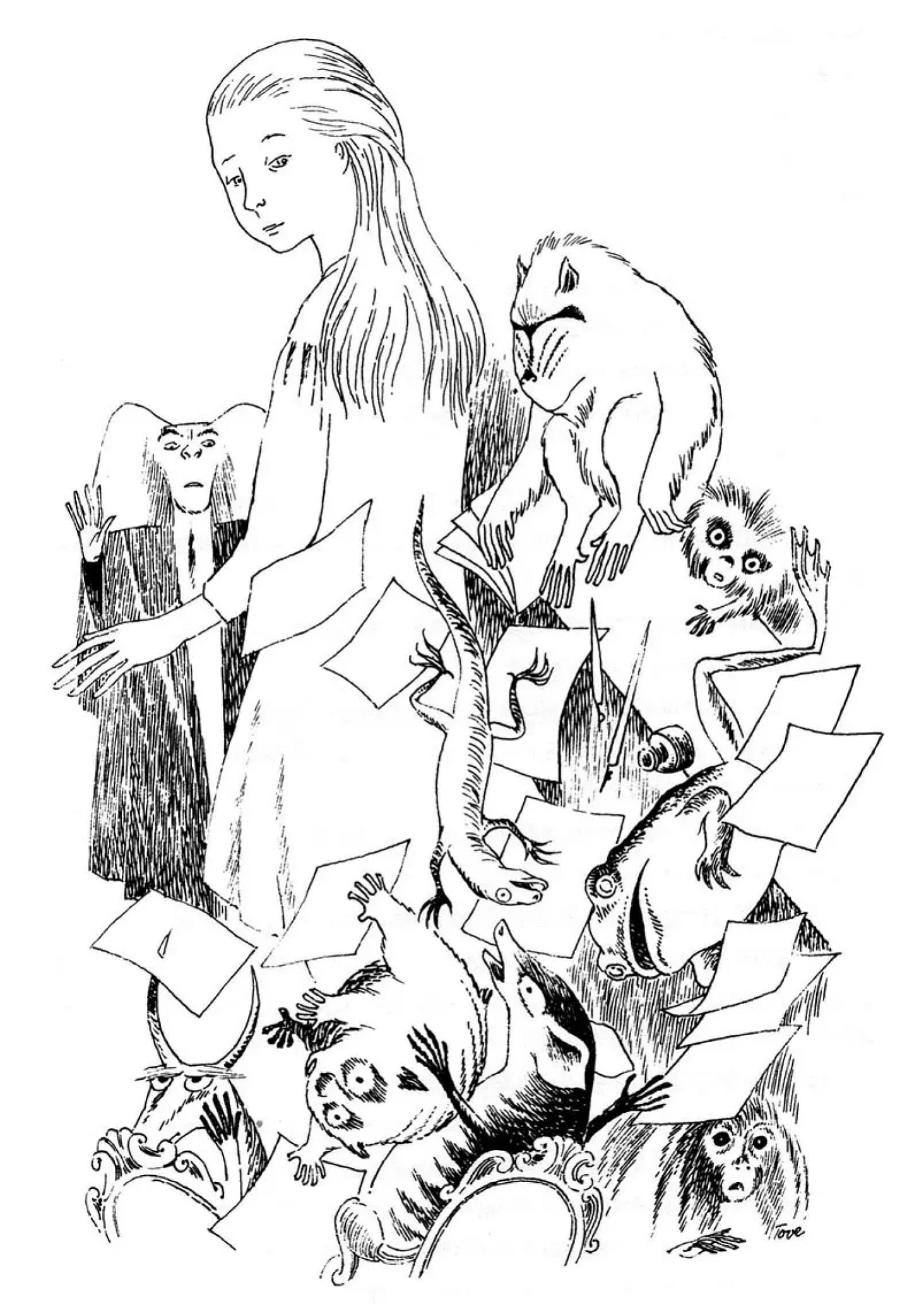

John Tenniel provided the original illustrations for Alice in Wonderland, bringing to such creatures as the dormouse and the dodo his keen naturalist eye. My mother gave me a version illustrated by the prolific children’s book artist Eric Kincaid, who added a soft and sentimental touch to the scenes, situating the mock turtle’s plaintive sighs in a desolate landscape. Soon I got my dad to buy me the published facsimile of Lewis Carroll’s original handwritten manuscript Alice’s Adventures Underground, with Carroll’s own illustrations. They are less artistically accomplished—the caterpillar looks like a knotted-up shoelace—but have their own awkward charm. And then Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice, with his notes on the mathematical games coded into the text, biographical anecdotes, and historical context. In high school: a grotesque, splattery Ralph Steadman edition. Years later, I acquired Alice in Space, by critic Gillian Beer, and just this year a colorful NYRB-issued version with Swedish artist Tove Jansson’s pictures infusing Wonderland with modern melancholy.

When I had the idea for this zine, I wasn’t thinking of my childhood. But I started to consider how reading a predetermined set of works—defined by author, or theme, or iterative versions of a single work—offers within that constraint a more freeing way of reading. (Or watching. Or listening.) Something more like how I started my life as a reader, without intentions or expectations. When I didn’t ask anything more of the book, or myself, than just to read it.

Camille Bromley reads and watches a lot of stuff.