This is entry #9 of Know-It-All, a zine about obsession and fandom. In this essay, Nicholas Russell writes about the prolific sci-fi novelist Gene Wolfe. Know-It-All zine is best read in print. To order a copy, go here.

I can’t remember how I came to Gene Wolfe and his sci-fi-noir novel A Borrowed Man. In my memory, like all of my favorite art, it seemed like it had always been there. Of course, that’s not strictly true. I’d heard Wolfe’s name tossed around by sci-fi nerds of a certain obsessive caliber, the kind who can’t countenance books that are popular or easy. And yet, Ursula K. Le Guin once called Wolfe “our Melville,” so he couldn’t have been too obscure. At any rate, I bought A Borrowed Man as soon as I cracked the book open and reached this sentence in the second paragraph: “You kept reading! All right, here we go.”

Direct address in fiction is a tricky thing. A little silly, a hint of overenthusiasm. As I delved deeper into Wolfe, I would learn that tricky things were his M.O. Like almost all of Wolfe’s work, A Borrowed Man is narrated by a male character whose naïveté and uncertainty about the veracity of his own account belies a startlingly shrewd perspective. Later in the novel, the complexity of this voice curdles into tangled confusion. Once I became a devotee I understood that a Wolfe novel nearly always subjects the reader to complete disorientation. The books travel from straight genre exercise to surrealist existentialism and back again. It’s this dense, chaotic quality, I assume, that prevents Wolfe from being so (too?) popular.

Like Le Guin, or James Tiptree Jr., or Cordwainer Smith, Wolfe is often treated as a writer’s writer, underestimated by academia and public alike. He worked as an industrial engineer while writing his first few novels, including The Fifth Head of Cereberus, which was stylistically influential beyond the bounds of genre. He drafted his opus, The Book of the New Sun, which was published over a period of seven years starting in 1980, in his spare time. Read enough of Seventies and Eighties-era sci-fi, horror, and fantasy authors, and invariably Wolfe’s name pops up on jacket copy and in acknowledgements. He holds Nebula, Locus, and World Fantasy awards. In 2012, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America named him their 29th Grand Master. During his lifetime, numerous old farts like Patrick O’Leary and Michael Swanwick deemed Wolfe the greatest living writer in English. This tension, between a kind of in-group protectiveness and a more general mass appeal, stalks Wolfe to this day. People seem to know him like I did: by name, but not necessarily by work.

Chief amongst Wolfe’s stylistic qualities is a textual playfulness, which muddies the waters between unreliability and misdirection. If one delves into his miscellany of letters to other writers and speeches given at awards ceremonies, like I have, a portrait of Wolfe emerges that parallels his characters: a writer who can’t help but tell the story from his perspective. I’m borrowing the metaphor from Wolfe during a 1983 self-interview titled “Lone Wolfe”: “You mean the mask I shave. That isn’t me.” The Gene Wolfe people talk to? “That’s not me either, or at least very seldom.”

I used to say that Wolfe is one of my favorite speculative fiction writers, but in fact he is one of my favorite writers, full stop. A truly strange and singular artist whose work is also difficult to recommend. (And maybe this too is another reason his work isn’t more widely known). It’s not that I don’t recommend him. I often talk about him in a needling way that implies that you should read him. It’s more that there are certain elements of his work, particularly male-female relationships, that give me pause. Or, I should say, they force me to think through what it is I like about him more than I normally would.

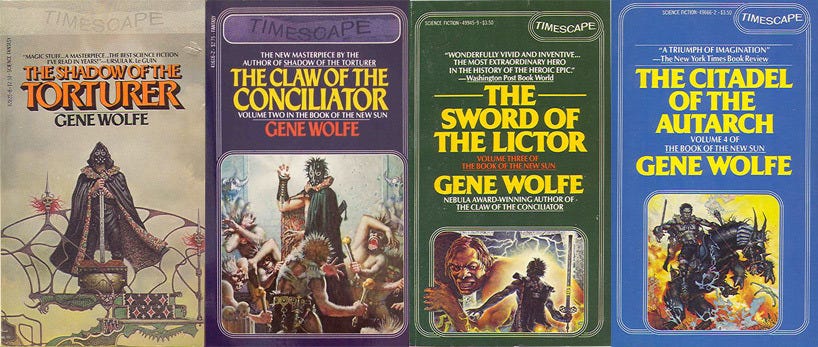

Every few years, for example, someone tweets out a call to read Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun, a tetralogy set on a future Earth that, in the wake of alien invasion and technological prosperity, has fallen into a dark age indistinguishable from medieval times. The protagonist, an executioner of the Order of the Seekers for Truth and Penitence named Severian, traverses the planet, and later time and space, in exile, after helping a a man escape torture by committing suicide. There are moments of coercion and abrupt violence in The Book of the New Sun that disturbed me when I read them, because they felt like abrupt changes in behavior and tone. It kept Severian’s motives murky, his characterization slippery.

Despite these not-so-palatable tendencies, it’s never occurred to me to stop reading Wolfe. I’ve yet to find many comparable stylists in the sci-fi/fantasy realm, writers who write beautifully without the sense that they are merely imitating their betters. In that 1983 self-interview, Wolfe says, “To interview me as you should, you ought not only to have read all my work (I am aware that you have) but also read widely in the field.” An ironic boast given that reading widely in the field renders most other works lackluster by comparison. I continue to be surprised by the emotional resonance of his work, which is sometimes opaque, uncomfortable, frightening. I think, at this stage of my life at least, the doubt in his fiction compels me.

Sci-fi and fantasy fandom tends to zealously overprotect writers just outside of the mainstream. Wolfe has been praised as a writer deserving the “same rapt attention we afford to Thomas Pynchon, Toni Morrison, and Cormac McCarthy,” so good he left Le Guin “speechless,” yet he nevertheless remains an acquired taste, his style idiosyncratic and his narrative proclivities unorthodox.

I now count over a dozen of Wolfe’s books on my shelf, not including vintage duplicates I’m still hunting for, but his bibliography is so extensive that I continue to discover stories, interviews, essays, photographs. He’s a perpetually found artist. I think this idea I have of him would make him happy. I recall another of his self-interviews from Castle of Days, in which Gene Wolfe discusses his creative process with himself. I see it as a mantra for reading him.

Q: Suppose you find out someday that you have lost it? What will you do then?

A: Go looking for it again. I found it once, why shouldn’t I find it again?

Q: Start over?

A: Start over.

Nicholas Russell is a writer and critic from Las Vegas. He is on Substack at eemaildotcom.

Wolfe endures. I am seeing his names more often. Perhaps I am looking. I would say he is superior to McCarthy in general and more prolific certainly. Blood Meridian is hard to top, however.